Bodies of Work, Series, and One-Offs in Fine Art Painting

Ok this is going to be a LOOOOOONNNNNGGG blog because I really wanted these information for myself to go back time and time again to remind myself EVERYTHING around “body of work”. Ready?

In the fine art world, painters often organize their creations into overarching bodies of work, focused series, and individual one-off pieces. Understanding these categories is crucial for grasping an artist’s practice and career development. Each category has a distinct purpose, typical scale (number of works), and role in how artists grow and how their work is received by galleries, curators, and collectors. This report defines each category in professional art terms, provides clear examples (including practices of artists Christian Hook and Nick Alm), and offers guidance for emerging painters on building a cohesive yet evolving artistic practice.

Defining a Body of Work

A body of work refers to a cohesive collection of artworks that share a consistent vision or set of elements, clearly representing the artist’s distinctive voice. In essence, it is the artist’s oeuvre or a significant subset of it, unified by common threads in content or style. An artist’s body of work typically maintains consistency across multiple aspects – for example, the subject matter, style, theme, color palette, medium, and presentation format – so that viewers can recognize the hand of the same creator in each piece. In practice, at least four of these elements tend to remain constant throughout a cohesive body of work, ensuring a level of unity.

Purpose and Career Function: Building a body of work is fundamental to refining an artist’s creative identity and showcasing their range within a coherent vision. For the artist, focusing on a body of work helps in “refining your voice and the direction of your practice” over the long term By concentrating on a central concept or approach and producing multiple works around it, painters learn through repetition with variation, discovering subtleties and developing mastery that a single piece could not teach. From a career perspective, a strong body of work is often a prerequisite for gallery representation and professional recognition. Galleries and curators want to see a committed vision: they prefer that potential collectors be able to identify an artist’s pieces at a glance as “recognisably yours”. A cohesive body of work signals that the artist has developed a clear artistic voice and can sustain it – a key marker of professionalism.

Typical Scope (Number of Pieces): There is no strict rule for how many works make up a body of work, but a common guideline is on the order of a dozen or more substantial pieces focused on a related idea. In practice, what constitutes a “sufficient” number can depend on the medium and the context. For a painter, many experts cite around 10–20 finished works as a minimum for a coherent portfolio or exhibition body. For instance, art coaches often mention 12 pieces as a starting target – enough to demonstrate depth – though a photographer or watercolorist might produce more, whereas an oil painter of large canvases might have fewer. The key is not a magic number but rather demonstrating that the artist can explore a concept in breadth and depth. Established artists may develop multiple bodies of work over their career (sometimes corresponding to different periods or themes in their development), each comprising dozens of works. An emerging artist’s first cohesive body of work might simply be the series of paintings that defined their initial style, whereas a mid-career painter might have several bodies of work reflecting evolving interests.

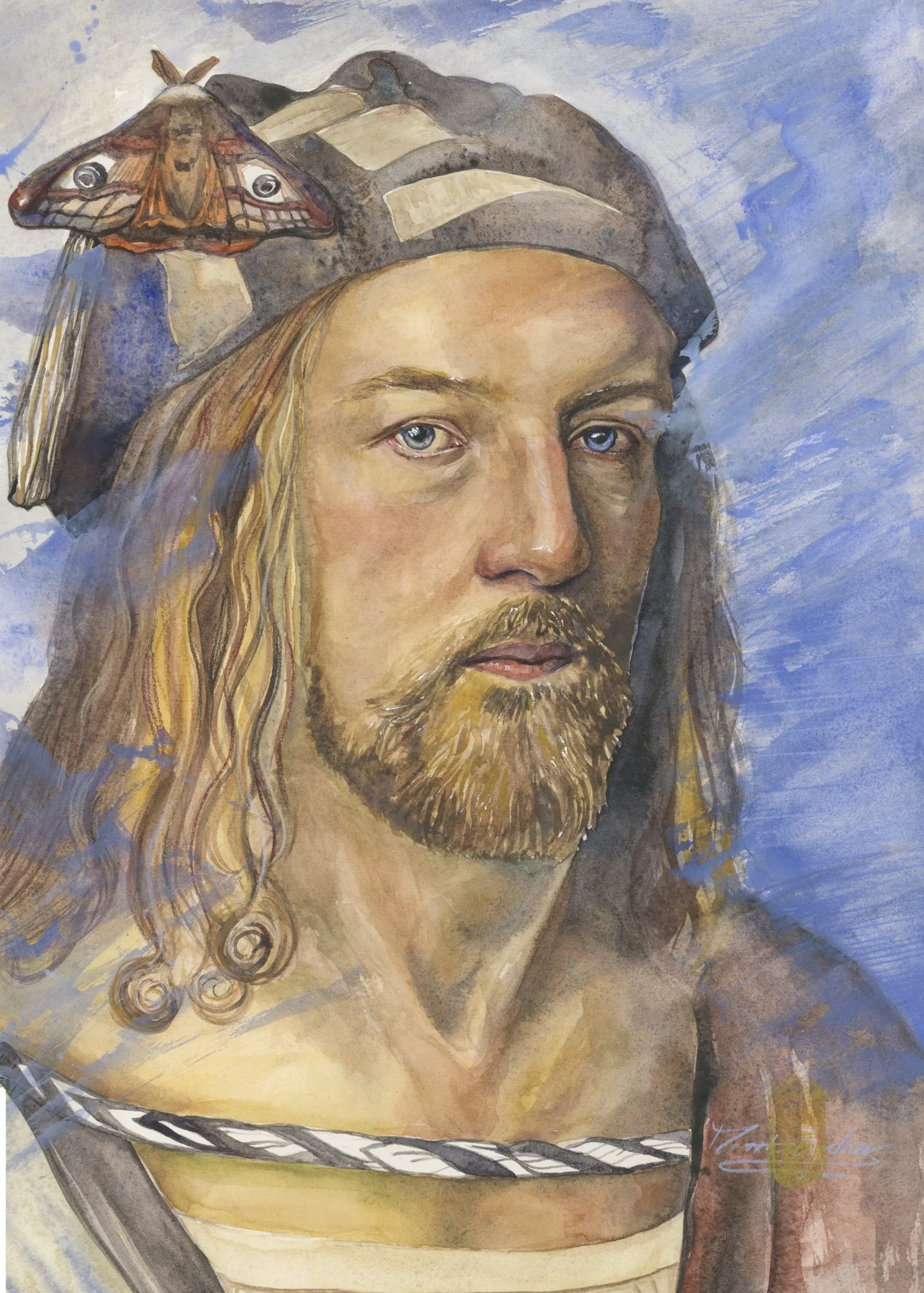

Figure: A painting by Nick Alm capturing the atmosphere of a café scene. Nick Alm’s oeuvre provides an example of a cohesive body of work grounded in a consistent vision. The Swedish painter is known for his expressive figurative scenes of social gatherings – from restaurants and cafés to dance floors – all rendered with a distinctive combination of classical technique and dreamy, emotive brushwork. Alm’s works share a recognizable style and subject focus: one could walk into a gallery and immediately identify a painting as a “Nick Alm” from the subtle interplay of figures and light. This unity of theme and approach means that, collectively, his paintings function as a strong body of work that “captures the subtleties of human body language in his expressive paintings”. Importantly, Alm’s body of work did not emerge overnight as a random assortment of one or two successful pieces, but through developing many related works over time. For a 2024 solo show in New York, he prepared around 20 new oil and watercolor paintings under the thematic title “Portals and Places,” essentially presenting a fresh body of work exploring intimate social moments in various settings. This volume and coherence of output helped solidify Alm’s reputation and gives curators and collectors confidence in the maturity of his practice.

In summary, the body of work is the cornerstone of an artist’s professional presence. It showcases consistency and commitment, allows an audience to fully engage with the artist’s ideas, and underpins career milestones like exhibitions and gallery signings. For an emerging painter, developing a cohesive body of work is often the first major step from student or hobbyist into the realm of a serious fine artist.

Series of Paintings

A series is a subset of an artist’s work – a group of paintings linked by a unifying idea or format – that forms a clearly identifiable family within the larger body of work. In other words, a series is a cohesive, unified body of work within the oeuvre. All pieces in a series share deliberate similarities, whether in subject matter, visual style, technique, palette, medium, or concept (often several of these in combination). If displayed together, it should be immediately obvious to the viewer that the works “are a related family”. Many painters create series as a way to deeply explore a particular theme or to push a concept to its limits across multiple canvases.

Purpose of a Series: Working in series allows artists to expound on a particular subject, concept or idea with breadth and depth. A single painting can only capture one moment or facet, whereas a well-developed series can approach the theme from multiple angles, creating a richer narrative or exploration. As artist Lynette Ubel explains, “with each additional painting in a series, the original thought grows into something more refined and bigger than a singular painting could ever be”. The series format thus amplifies the artist’s voice – each piece reinforces the others, making the overall artistic statement “louder and clearer”.

From the viewer’s or collector’s perspective, a series provides insight into the artist’s creative process and intentions. Seeing a group of related works together helps the audience grasp what the artist is “trying to convey” by witnessing how a theme is “stated and restated in different yet interconnected ways”. For example, if a painter is fascinated by the changing light at dusk, a series might include multiple canvases of the same motif at different times or seasons – collectively giving the viewer a comprehensive sense of that fascination. Series often form the basis of solo exhibitions and gallery shows, since they present a unified experience rather than a disparate mix.

Typical Size of a Series: Series can vary widely in length – from a handful of pieces to dozens – depending on the artist’s goals and the nature of the project. Some series are intentionally small (for instance, a trilogy of works forming a triptych-like narrative), while others grow over years. Professional artists often continue adding to a successful series until they feel the exploration is complete. In practice, contemporary painters might create series in the range of perhaps 5 to 20 paintings for a given exhibition, though some prolific artists or long-term projects can yield many more. In an educational article, painter Arrachme wrote that she generally stopped at around 30 paintings for a series, noting that galleries early in her career wanted to see on the order of dozens of works to consider the series “proper” and exhibition-ready. Not every series must be that large, but the implication is that a series is more than just two or three similar pieces; it requires a commitment to multiple iterations on a theme. Indeed, a series is distinct from a simple diptych or triptych (a set of 2 or 3 directly connected images) – those are essentially one artwork split into panels, whereas a series is a looser grouping of stand-alone works that collectively articulate an idea.

Common Unifying Factors in a Series: Artists may choose a variety of constraints or motifs to tie a series together. These could include:

Subject or Theme: e.g. all paintings depict urban street scenes, or all explore a mythological story.

Technique and Style: e.g. a particular painting method, such as a stippling technique or a collage of abstract textures, used consistently.

Color Palette: e.g. a series might be defined by a narrow range of colors (monochromatic blue works, or a recurring set of tones).

Medium and Format: e.g. all works made in oil on the same size canvas, or all are circular panels.

Conceptual Approach: e.g. investigating the concept of memory, each piece representing a different memory in a similar conceptual framework.

However, these unifying elements are not rigid rules; many series find unity through a mix of factors. The guiding principle is that there is a “common thread” that connects the works, creating a sense of continuity. For instance, Christian Hook, an award-winning contemporary painter, often works in clearly delineated series. In an interview, Hook noted, “In each series I work on, I like to explore entirely new materials and techniques”. This indicates that while the conceptual theme of each series differs (one series might be about classical horses and modern technology, another about personal memories), the works inside that series share the specific methods and ideas Hook decided to use for that project.

Figure: Christian Hook’s “Bather Kneeling in Digital Bath,” part of his Electronic Paintings series (mixed media, 94×94 cm). This artwork is from Hook’s recent series fusing classical figurative painting with digital motifs. In the Electronic Paintings series, inspired by electronic music and modern technology, Hook created layered compositions where realistic figures merge with abstract, pixelated forms. In this piece, the nude and the geometric outline of a bathtub appear fragmented by digital “glitches” and translucent layers of color. All paintings in this series reflect Hook’s interest in the intersection of classical art and contemporary digital aesthetics, sharing a similar palette of muted greys and soft greens accented by neon highlights, and a technique of blending finely rendered anatomy with bold abstract passages. Exhibited together, these works form a compelling series with a unified look and concept – what one reviewer called an “innovative series capturing the essence of electronic music through multi-dimensional, AI-enhanced portraits” (though the pieces are visual, the concept was influenced by music and technology). Hook’s approach exemplifies how a series functions: each painting stands on its own, but together they “bring order to chaos” and fully express the artist’s fascination with time, motion, and modern media. Notably, Hook tends to name and publicize his series as distinct projects. For example, he has produced series like “Electronic Paintings,” “No Mud No Lotus,” and “Drawings from Somewhere Else,” each with its own theme and style explorations (often coinciding with a new exhibition or phase of his career). This practice of working in series has helped Hook continually rejuvenate his creative output while still keeping each project cohesive internally.

Series in a Painter’s Career: Developing series is a common strategy for sustaining a long-term art career. Many respected artists move from series to series over the years, each series marking a chapter in their artistic evolution. This allows them to innovate and challenge themselves (by tackling new themes or techniques in the next series) without alienating their audience (because each series is internally consistent and recognizable). Christian Hook articulates this balance well: he rarely repeats materials or methods between series, treating each new series as a fresh experiment, yet each body of work is “unmistakably” his own in its fundamental sensibilities. Similarly, Nick Alm’s gallery shows could be seen as series centered on particular settings or moods – one exhibition might focus on intimate indoor scenes, another on lively outdoor parties – all within his signature figurative style. By working in series, artists also create opportunities for collectors to engage more deeply: some collectors might acquire multiple works from a series they love, and galleries often prefer to exhibit a series because it tells a coherent story in the gallery space. In fact, gallerists often encourage artists to produce series or at least maintain consistency, as it helps in marketing the artist and building a “recognizable style in the art market”. A series that is “done well speaks to the breadth and scope of an artist’s abilities” while also proving they can sustain an idea beyond one canvas.

It’s important to note that while series are beneficial, they are not absolutely mandatory for success – some artists gain recognition through a very consistent style even if they don’t label their works into explicit series. The overarching goal is consistency and quality; thinking in series is simply a powerful way to achieve that. As gallery owner Jason Horejs explains, “working in series is not [an absolute requirement]. Many artists attain representation based on the strength of their style and quality… without creating work that could truly be called a series”. Nonetheless, he goes on to acknowledge that if an artist’s work does lend itself to series, embracing that can add an “extra level of interest” and draw in collectors who may “want to have multiple pieces from the series.”. In summary, series are valuable tools in a fine art painter’s arsenal: they demonstrate dedication, invite deeper engagement, and structure an artist’s progression in a meaningful way.

One-Off Works

In contrast to an extensive body of work or a deliberate series, a one-off painting is a stand-alone piece created in isolation from other works, not intended as part of an ongoing theme or set. A one-off could be an experimental artwork, a special commission, or simply a singular idea the artist pursued once. These pieces are unique in subject or approach relative to the artist’s other output. For example, an artist known for landscapes might do a one-off portrait as a commission for a patron – a departure from their usual practice, not to be repeated frequently. One-off works are common in every artist’s journey, especially during periods of exploration or transition.

Purpose and Role of One-Offs: One-off paintings often serve as explorations or testing grounds. Many series begin with a one-off: an artist tries a new motif or technique in a single canvas; if it resonates, that “lone isolated work” can become the seed for a full series or a new body of work. Lynette Ubel notes that these one-offs are “many times an artist’s exploration on the path to a theme, direction and, in the end… a series”. In this sense, one-offs are like sketches for the mind – they allow freedom without the commitment of a whole project. Artists sometimes fear that committing to one style might be limiting or “pigeonholing”, so a one-off can be a way to break out momentarily or inject variety. However, rather than causing boredom, a well-chosen one-off experiment can invigorate an artist’s creativity. In Ubel’s experience, having a clear direction (a series) is actually “freeing” – the blank canvas is less scary because you have a framework – whereas endless one-offs with no through-line can be more daunting. The key is that one-offs, when done intentionally, can refresh an artist’s practice or open new avenues, so long as the artist eventually finds how (or if) that experiment fits into their broader work.

Another common purpose for one-offs is fulfilling external opportunities. Commissioned paintings are often one-offs by nature: for instance, when Christian Hook won the Sky Arts Portrait Artist of the Year in 2014, he was suddenly commissioned to paint portraits of notable figures like Sir Ian McKellen and Dame Judi Denchl. These portraits were prestigious stand-alone projects, not part of Hook’s personal thematic series, yet they played a significant role in his career by boosting his visibility and credibility. One-off pieces can also be created for charity auctions, special events, or as demonstrations. Fine artists sometimes produce one-off works for art fairs or open studios – pieces that might be a bit outside their usual series, meant to attract a different segment of the audience or to try a whimsical idea once.

One-Offs in a Career Context: While one-off works can be important and even career-defining (a single iconic painting can make an artist’s name), emerging artists must use them strategically. Galleries and collectors tend to evaluate an artist based on consistency and the development of themes. If an artist’s portfolio is entirely made up of unrelated one-off pieces – a landscape here, a surreal abstraction there, a portrait somewhere else – it becomes difficult for professionals to discern what the artist is really about. As art advisor Allan Duerr put it succinctly, “Known artists are known for a body of work – not for ‘one-off’ works”. A body of work demonstrates a sustained philosophy and expression, whereas scattered one-offs, especially early in a career, might signal that the artist hasn’t yet found their focus. Therefore, many experts advise artists to avoid showcasing too many disparate one-offs when trying to establish themselves. Instead, they should concentrate on a coherent group (even if modest in size) that defines their style, and perhaps keep the outlier experiments in the studio or sketchbook until they see how to integrate them.

That said, one-offs can certainly be included in exhibitions or portfolios as highlights or wild cards – particularly if they are exceptionally strong pieces or illustrate a point of growth. Curators sometimes enjoy including an unexpected piece to show another side of an artist, but usually only after the artist is recognized for a primary mode of work. From a collector’s viewpoint, a one-off can be attractive if it’s a spectacular example of the artist’s skill or imagination. Some collectors specifically seek unique pieces that stand apart. However, even those unique works typically carry the artist’s signature style in some way. For example, Nick Alm largely sticks to his figurative social scenes, but if he were to paint, say, a standalone allegorical portrait or a pure landscape as a one-off, it would likely still be handled with the same velvety realism and subtle emotive quality present in his other works, making it identifiable as Nick Alm’s hand. Thus, one-off does not necessarily mean “out of character” – it simply means not part of a series or repeated theme.

In Christian Hook’s case, one-off endeavors like his high-profile commissioned portraits augmented his main practice. They did not detract from the coherence of his personal work, because alongside these he continued to produce series-driven projects that defined his artistic identity (for instance, even as he completed the commissioned Portrait of Alan Cumming – a prize from the competition – he was developing new experimental series on his own initiative). In fact, one of Hook’s recent celebrated projects, “Drawings from Somewhere Else,”began as a very personal one-off response to the loss of a friend, which then evolved into a collection of works so impactful they were exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery. Initially sketched on an iPad in solitude, those pieces became a “deeply emotional body of work” exploring memory and farewell. This illustrates how an idea might start as a singular cathartic artwork and grow into a fully-realized series (in this case, bridging digital and traditional media) once the artist recognizes its potential and depth.

In summary, one-offs are the individual sparks in an artist’s practice – sometimes they remain solitary, other times they ignite something bigger. They are valuable for experimentation, for seizing opportunities, and for occasional variety. Yet, for professional growth, one-offs should be balanced with and eventually absorbed into a larger narrative of the artist’s work. Artists gain the most traction when those solitary experiments inform or enhance their main body of work, rather than scatter it.

Other Key Distinctions and Terminology

When discussing bodies of work and series, a few other terms often come up in the fine art context:

Oeuvre: This French term refers to the entire body of work produced by an artist over their lifetime. One can speak of “the oeuvre of Christian Hook” meaning all of his creations to date. An oeuvre may encompass multiple bodies of work or periods. For example, Nick Alm’s oeuvre includes his early atelier studies, his mature social scenes, and any other explorations he’s done – effectively everything as a whole. Critics and historians look at an oeuvre to assess an artist’s overarching themes and evolution.

Collection (in two senses): The word “collection” can be confusing in art. In strict terms, a collection refers to an accumulation of artworks, typically by an institution or individual collector. For instance, the Morse Collection of Dalí paintings or a museum’s collection of contemporary art. However, artists and galleries sometimes colloquially use “collection” to mean a set of new works for an exhibit (much like a fashion designer presents a “collection” each season). To avoid ambiguity, it’s helpful to use “series” or “body of work” for an artist’s grouping, and reserve “collection” for collected works by owners. As an example of correct usage: Clarendon Fine Art might display a collection of Christian Hook’s works, but within that display he might have the Electronic Paintings series. In Arrachme’s explanation, “a series refers to a cohesive unified body of work”by the artist, whereas a collection in art-speak is a set of works someone has collected. Emerging artists should be aware of this distinction when describing their portfolios to galleries or writing statements.

Triptych/Diptych: These terms describe single artworks composed of separate panels (three for a triptych, two for a diptych). They are not series in the sense we’ve discussed, but rather one piece in multiple parts. For example, if a painter creates one large image split into three canvases meant to hang together, that’s a triptych, not a series of three independent paintings. Triptychs are a classical format (used in altarpieces, for instance) and are still used today to give a panoramic or sequential effect within one artistic statement. It’s worth noting so as not to confuse a “series of three paintings” with a “three-part painting.” A series could certainly contain a triptych as one of its works, but generally series implies each piece stands alone.

Studies and Sketches: Artists often create preliminary studies, sketches, or smaller experimental works while developing a series or larger piece. These might be one-off in nature, but they function as supportive work rather than finished pieces for display (though sometimes artists do exhibit their studies, framing them as insight into their process). For instance, Christian Hook might do quick studies of horse motion or a person’s face as preparation for a larger composition in his series. These studies aren’t considered part of the final body of work or series, but they are part of the process. Galleries typically present finished series, but occasionally an exhibition might include a study or two to illustrate the development. Collectors sometimes also value studies if they relate to a famous work.

In essence, understanding these distinctions helps in navigating conversations in the art world. An emerging painter should be comfortable explaining, for example, that “this painting is a one-off experiment” versus “this painting is part of my X series, which is a new body of work I’m developing.” Mastery of such terminology not only clarifies the artist’s intentions but also signals professionalism to curators and collectors.

Building a Cohesive yet Evolving Practice: Advice for Emerging Artists

For artists at the start of their fine art careers, the concepts of bodies of work, series, and one-offs are not just abstract labels – they are practical tools for growth. How you balance consistency with creativity can shape your artistic identity and your success in the art market. Below are key considerations and strategies for emerging painters, framed around the categories discussed, to help develop a practice that is both cohesive and evolving:

Build a Cohesive Body of Work: As a new artist, aim to create a core group of artworks that truly represent your artistic voice. This means zeroing in on subjects and techniques you are passionate about and executing a number of works (perhaps 10 or more to start) that share common elements. Remember that cohesion doesn’t mean monotony – it means there are connecting threads. It could be a consistent style or mood even if the subjects vary. The goal is that if a curator places your works in a room, they feel like they “belong” together. This coherent body of work is your calling card. It shows you have direction and can produce beyond a one-hit wonder. It’s often better to have a smaller but tightly unified portfolio than a larger inconsistent one when approaching galleries. Keep in mind, galleries nearly always prefer to see a “clear, cohesive body of work” before considering an artist – this demonstrates professionalism and readiness. So, focus your energies on a defined project or theme that can anchor your early career. You can still make other things (in fact, you should experiment on the side), but curate what you show publicly to emphasize coherence.

Develop Series with Purpose: Once you have a general direction, consider working in series to dive deeper into your chosen ideas. Creating a series means deciding on a concept or a set of limitations and producing multiple works under that umbrella. For an emerging painter, committing to a series can be a great way to overcome the blank canvas syndrome – you have a starting plan for each new work. As you add pieces, you might find the idea “takes on a life of its own,” growing in ways you didn’t expect. Plan a series when you notice a particular subject or approach truly excites you and has more to give. For example, you painted one nocturnal cityscape that came out well; perhaps make it a series “City at Night” with different landmarks or different weather. Why do this? Because it will demonstrate depth. As noted earlier, a series shows you can “recreate and reinterpret an idea” multiple times, which signals to others that you have mastery and consistency. It also makes it easier to present your work: a gallery can envision a show “featuring 10 paintings from your XYZ series” more readily than 10 unrelated pieces. When planning a series, think about scope – it need not be 30 paintings as Arrachme suggested for a fully developed series, but ensure it’s enough to make an impact (a half-dozen at minimum is a good rule of thumb for a small series, whereas a dozen forms a strong full series for an exhibition). Each series you complete as a young artist becomes a building block in your resume and portfolio. Over time, these series might collectively form your larger body of work, or mark stepping stones as your style evolves.

Use One-Offs Wisely: One-off pieces – those outside of any series – should be approached deliberately. Early in your development, you will likely create many one-off works as you experiment with different genres and techniques. That’s a natural part of finding your voice. But when it comes to showcasing your art or proposing yourself to a gallery, be selective. It’s often wise to keep the most disparate one-offs in the background until you establish a coherent line of work. This doesn’t mean you should suppress your creativity – by all means, explore! – but understand how it appears to others. If you have an urge to try something radically different, do it as a learning exercise or a private commission, and then reflect: does it align with or inform your main direction? If yes, perhaps it can be integrated or even start a new series; if not, it can remain a standalone experiment. Strategically, one-offs are excellent for testing new waters or taking a mental break. For instance, Christian Hook ventured into sculpting or digital art in isolated cases as experiments, but he eventually folded some of those insights back into his painting practice. If a one-off painting turns out exceptionally well and you love it, consider if it deserves companions – that’s how many great series begin. On the other hand, if you do a one-off purely to please a client (e.g. a portrait commission far from your usual subject matter), don’t feel obligated to make it part of your portfolio identity. You can proudly show it as an example of skill, but clarify it’s a special case. Many artists have a section in their portfolio for “commissions” or “divergent works,” separate from their main gallery works. In summary, prioritize developing series and bodies of work for public display, and channel one-off explorations in ways that ultimately strengthen those larger bodies.

Maintain Cohesion While Evolving: One of the biggest challenges for an emerging artist is how to grow and change without losing the thread that made their work unique in the first place. The key is to evolve within a framework. Use each new series or project to introduce something fresh – a new technique, a new theme – but keep other aspects consistent. For example, you might carry over your distinctive brushwork and color sensibility even as you shift from painting interiors to painting figures. Jason Horejs’ consistency checklist is useful here: try to keep at least 4 out of 6 elements (subject, style, theme, palette, medium, presentation) consistent across a body of work. When you decide to change things, don’t change everything at once. Christian Hook’s method is illustrative: for each series he changes materials and explores a new concept, but one can still tell it’s the same artist because his underlying interest in layering imagery and capturing time is a through-line. Think of your work like a novel – you want multiple chapters (series), each distinct, but all written in your voice. It’s wise to let your audience transition with you. If Nick Alm suddenly painted in a cubist style, it would shock those who know his work; instead, his evolution has been gradual – he may experiment with looser backgrounds or different social settings, but the core figurative approach remains. Over time, your practice will broaden (perhaps significantly), but early on, build a solid foundation. Once you have a recognized strength, you have more leeway to push boundaries. You can even explicitly signal new directions by grouping new experiments as a “new series” – that prepares viewers to expect something different yet related. Strategically, if you feel you’ve mastered one theme and are getting restless, plan your next series to challenge yourself in one dimension while retaining familiarity in others. This way your work stays cohesive and recognizable, yet you don’t stagnate artistically.

Understand Curatorial and Market Perspectives: It helps to put yourself in the shoes of those who will be evaluating or buying your art. Curators and gallery owners generally look for consistency, quality, and a narrative they can present. A curator assembling a show might think in terms of series or bodies of work – they may ask, “Does this artist have a coherent body we can exhibit? What story do these works tell together?” If you have a well-developed series, it’s much easier for them to say yes. In fact, to secure a solo show, you typically need enough works of a kind to fill a space and a clear concept tying them, which is essentially a series or unified body of work. Galleries often test emerging artists in group shows first; having a few pieces that strongly relate (and stand out as yours) in a group setting can catch a curator’s eye. Collectors, on their side, are diverse: some seek a representative piece from an artist they like, others become avid followers and purchase multiple works across different series. When you are unknown, collectors will be taking a risk on you, so they often prefer to see a track record of consistency. It reassures them that the piece they buy isn’t a fluke and that you are likely to continue producing valuable work (which can affect the long-term value of what they own). As noted in one illustration industry commentary, showing only one piece gives little insight, but showing a series proves that you can “repeat past successes reliably” – something that offers security to buyers. Once you gain collectors who love a certain series, they may actually encourage you to continue in that vein or look forward to your next series. It’s a fine balance: you want to keep your collectors interested by evolving, but not alienate them with abrupt changes. Communication can help; for instance, explaining in an artist statement how your new series grows out of the previous one can bring collectors and curators along on the journey. Additionally, keep in mind that while a bold one-off might grab attention (a spectacular huge painting could make a splash at an art fair), what ultimately sustains interest is the context of your other work. Curators often assess whether an impressive single piece is backed by “legs” – i.e. a whole body of substance behind it. Thus, to impress the art world, cultivate depth, not just isolated moments of brilliance.

Prioritize Artistic Growth and Professional Presentation: In practical terms, emerging painters should focus on two parallel tracks – artistic development and professional development – and the idea of building bodies of work and series ties into both. Artistically, challenge yourself to push a theme further (can I make 5 more variations of this idea? what will I learn on the way?). Set project goals, like “This season I will complete an 8-piece series exploring reflections in water.” Such self-directed briefs can mimic the structure of assignments and force you to think in series. Professionally, document and present your work in coherent groupings. It’s useful to organize your portfolio or website by series or projects, rather than a mishmash chronologically. Write a brief statement for each series/body of work explaining its concept; this helps curators see the intentionality. Keep your body of work at the forefront when you approach galleries – for example, a concise PDF or webpage showing 10-15 works that clearly go together, with one or two detail shots or one-offs as spice perhaps. Also, don’t underestimate the value of consistency in things like titles and framing – they contribute to that sense of a unified body. If all your series paintings have related titles or the same framing style, it further signals that cohesion. In terms of growth, be patient. Early in a career, depth matters more than breadth. It might be tempting to show you can do everything (portraits, landscapes, still life, abstract) to not miss any opportunity, but most successful fine artists build a strong reputation in one area first and later branch out. As the saying goes, you have to be known for something before you can be known for something else. So, find that something (your niche, however broad or narrow) and develop it fully. Lastly, seek feedback from mentors or peers on whether your work reads as cohesive. Sometimes an outside eye can tell you which pieces look out of place. Curate yourself ruthlessly – it’s better to present 8 excellent, tightly related works than 8 plus 2 mediocre outliers that dilute the impact.

By prioritizing these strategies, emerging artists can create a practice that feels genuine to their interests while also meeting the expectations of the fine art world. Christian Hook and Nick Alm’s examples reinforce these lessons: Hook gained prominence by presenting a strong series (his prize-winning portrait work led to bodies of work that explored new concepts), and he continually rejuvenates his practice through series that each build on the last in some way. Nick Alm developed a clear figurative voice and stuck to it, producing one elegant painting after another until a critical mass of work spoke for him – now his evolving series of social scenes have made him a sought-after name in figurative art. Both artists showed that one can grow (experimenting with AI imagery in Hook’s case, or shifting social narratives in Alm’s) without losing the core of what makes their work identifiable and compelling.

In conclusion, think of body of work as your legacy in progress – each painting you create either contributes to it or guides you to adjust it. Use series to structure your explorations and convey your ideas with power and clarity. Allow one-offs to spark creativity and respond to opportunities, but weave their insights back into your main tapestry. Over time, you will have not just a random assortment of paintings, but an integrated, rich artistic practice. This cohesive yet ever-evolving approach will help you grow both artistically and professionally, positioning you for longevity in the fine art world.

Sources: The analysis above integrates insights from professional art commentary and examples. Notably, definitions and advice on developing cohesive work draw on Jason Horejs’s gallery expertise and artist Lynette Ubel’s perspective on series vs. one-offs. The practices of Christian Hook and Nick Alm are referenced to illustrate how these concepts play out in real fine art careers – for instance, Hook’s Electronic Paintingsseries and commissioned portraits, and Alm’s consistent thematics in his body of work. These examples and references support the guidance provided for emerging artists, underlining the importance of a coherent yet dynamic body of work in the fine art world.

This diagram breaks down how painters structure their work:

A Body of Work is a cohesive, recognizable group of paintings that defines an artist’s voice.

Within it, a Series is a focused set of 3–12 related paintings exploring a specific theme or visual idea.

One-Offs are single, standalone paintings — often making up over 65% of an artist’s output — not tied to a series but still aligned with their broader style.

Studies are exploratory pieces, typically 2–6 per painting or concept, created to test composition, technique, or color before starting a final work.

This breakdown helps emerging artists focus on consistency, depth, and intentionality — the hallmarks of a professional fine art practice.